I promised myself I wouldn’t go on for thousands and thousands of words about the Lingula genome paper (I’ve got things to do, and there is a LOT of stuff in there), but I had to indulge myself a little bit. Four or five years ago when I was a final year undergrad trying to figure out things about Hox gene evolution, I would have killed for a complete brachiopod genome. Or even a complete brachiopod Hox cluster. A year or two ago, when I was trying to sweat out something resembling a PhD thesis, I would have killed for some information about the genetics of brachiopod shells that amounted to more than tables of amino acid abundances. Too late for my poor dissertations, but a brachiopod genome is finally sequenced! The paper is right here, completely free (Luo et al., 2015). Yay for labs who can afford open-access publishing!

In case you’re not familiar with Lingula, it’s this guy (image from Wikipedia):

In a classic case of looks being deceiving, it’s not a mollusc, although it does look a bit like one except for the weird white stalk sticking out of the back of its shell. Brachiopods, the phylum to which Lingula belongs, are one of those strange groups no one really knows where to place, although nowadays we are pretty sure they are somewhere in the general vicinity of molluscs, annelid worms and their ilk. Unlike bivalve molluscs, whose shell valves are on the left and right sides of the animal, the shells of brachiopods like Lingula have top and bottom valves. Lingula‘s shell is also made of different materials: while bivalve shells contain calcium carbonate deposited into a mesh of chitin and silk-like proteins,* the subgroup of brachiopods Lingula belongs to uses calcium phosphate, the same mineral that dominates our bones, and a lot of collagen (again like bone). But we’ll come back to that in a moment…

One of the reasons the Lingula genome is particularly interesting is that Lingula is a classic “living fossil”. In the Paleobiology Database, there’s even an entry for a Cambrian fossil classified as Lingula, and there are plenty of entries from the next geological period. If the database is to be believed, the genus Lingula has existed for something like 500 million years, which must be some kind of record for an animal.** Is its genome similarly conservative? Or did the DNA hiding under a deceptively conservative shell design evolve as quickly as anyone’s?

In a heroic feat of self-control, I’m not spending all night poring over the paper, but I did give a couple of interesting sections a look. Naturally, the first thing I dug out was the Hox cluster hiding in the rather large supplement. This was the first clue that Lingula‘s genome is definitely “living” and not at all a fossil in any sense of the word. If it were, we’d expect one neat string of Hox genes, all in the order we’re used to from other animals. Instead, what we find is two missing genes, one plucked from the middle of the cluster and tacked onto its “front” end, and two genes totally detached from the rest. It’s not too bad as Hox cluster disintegration goes – six out of nine genes are still neatly ordered – but it certainly doesn’t look like something left over from the dawn of animals.

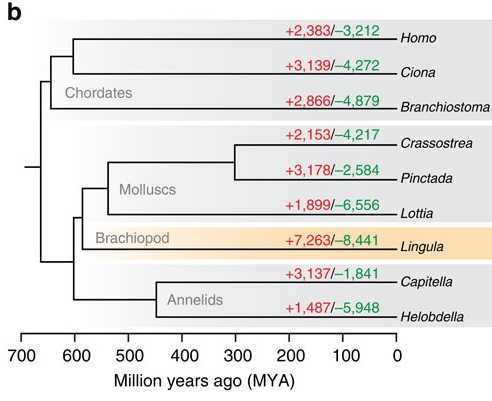

The bigger clue that caught my eye, though, was this little family tree in Figure 2:

The red numbers on each branch indicate the number of gene families that expanded or first appeared in that lineage, and the green numbers are the families shrunk or lost. Note that our “living fossil” takes the lead in both. What I find funny is that it’s miles ahead of not only the animals generally considered “conservative” in terms of genome evolution, like the limpet Lottia and the lancelet Branchiostoma, but also the sea squirt (Ciona). Squirts are notorious for having incredibly fast-evolving genomes; then again, most of that notoriety was based on the crazily divergent sequences and often wildly scrambled order of its genes. A genome can be conservative in some ways and highly innovative in others. In fact, many of the genes involved in basic cellular functions are very slow-evolving in Lingula. (Note also: humans are pretty slow-evolving as far as gene content goes. This is not the first study to find that.)

So, Lingula, living fossil? Not so much.

The last bit I looked at was the section about shell genetics. Although it’s generally foolish to expect the shell-forming gene sets of two animals from different phyla to be similar (see my first footnote), if there are similarities, they could potentially go at least two different ways. First, brachiopods might be quite close to molluscs, which is the hypothesis Luo et al.‘s own treebuilding efforts support. Like molluscs, brachiopods also have a specialised mantle that secretes shell material, though having the same name doesn’t mean the two “mantles” actually share a common origin. So who knows, some molluscan shell proteins, or shell regulatory genes, might show up in Lingula, too.

On the other hand, the composition of Lingula’s shell is more similar to our skeletons’. So, since they have to capture the same mineral, could the brachiopods share some of our skeletal proteins? The answer to both questions seems to be “mostly no”.

Molluscan shell matrix proteins, those that are actually built into the structure of the shell, are quite variable even within Mollusca. It’s probably not surprising, then, that most of the relevant genes that are even present in Lingula are not specific to the mantle, and those that are are the kinds of genes that are generally involved in the handling of calcium or the building of the stuff around cells in all kinds of contexts. Some of the regulatory mechanisms might be shared – Luo et al. report that BMP signalling seems to be going on around the edge of the mantle in baby Lingula, and this cellular signalling system is also involved in molluscan shell formation. Then again, a handful of similar signalling systems “are involved” in bloody everything in animal development, so how much we can deduce from this similarity is anyone’s guess.

As for “bone genes” – the ones that are most characteristically tied to bone are missing (disappointingly or reassuringly, take your pick). The SCPP protein family is so far known only from vertebrates, and its various members are involved in the mineralisation of bones and teeth. SCPPs originate from an ancient protein called SPARC, which seems to be generally present wherever collagen is (IIRC, it’s thought to help collagen fibres arrange themselves correctly). Lingula has a gene for SPARC all right, but nothing remotely resembling an SCPP gene.

I mentioned that the shell of Lingula is built largely on collagen, but it turns out that it isn’t “our” kind of collagen. “Collagen” is just a protein with a particular kind of repetitive sequence. Three amino acids (glycine-proline-something else, in case you’re interested) are repeated ad nauseam in the collagen chain, and these repetitive regions let the protein twist into characteristic rope-like fibres that make collagen such a wonderfully tough basis for connective tissue. Aside from the repeats they all share, collagens are a large and diverse bunch. The ones that form most of the organic matrix in bone contain a non-repetitive and rather easily recognised domain at one end, but when Luo et al. analysed the genome and the proteins extracted from the Lingula shell, they found that none of the shell collagens possessed this domain. Instead, most of them had EGF domains, which are pretty widespread in all kinds of extracellular proteins. Based on the genome sequence, Lingula has a whole little cluster of these collagens-with-EGF-domains that probably originated from brachiopod-specific gene duplications.

So, to recap: Lingula is not as conservative as its looks would suggest (never judge a living fossil by its cover, right?) We also finally have actual sequences for lots of its shell proteins, which reveal that when it comes to building shells, Lingula does its own thing. Not much of a surprise, but still, knowing is a damn sight better than thinkin’ it’s probably so. We are scientists here, or what.

I am Very Pleased with this genome. (I just wish it was published five years ago 😛 )

***

Notes:

*This, interestingly, doesn’t seem to be the general case for all molluscs. Jackson et al. (2010) compared the genes building the pearly layer of snail (abalone, to be precise) and bivalve (pearl oyster) shells, and found that the snail showed no sign of the chitin-making enzymes and silk type proteins that were so abundant in its bivalved cousins. It appears that even within molluscs, different groups have found different ways to make often very similar shell structures. However, all molluscs shells regardless of the underlying genetics are predominantly composed of calcium carbonate.

**You often hear about sharks, or crocodiles, or coelacanths, existing “unchanged” for 100 or 200 or whatever million years, but in reality, 200-million-year-old crocodiles aren’t even classified in the same families, let alone the same genera, as any of the living species. Again, the living coelacanth is distinct enough from its relatives in the Cretaceous, when they were last seen, to warrant its own genus in the eyes of taxonomists. I’ve no time to check up on sharks, but I’m willing to bet the situation is similar. Whether Lingula‘s jaw-dropping 500-million-year tenure on earth is a result of taxonomic lumping or the shells genuinely looking that similar, I don’t know. Anyway, rant over.

***

References:

Jackson DJ et al. (2010) Parallel evolution of nacre building gene sets in molluscs. Molecular Biology and Evolution 27:591-608

Luo Y-J et al. (2015) The Lingula genome provides insights into brachiopod evolution and the origin of phosphate biomineralization. Nature Communications 6:8301

Great article. I’m curious about one thing though.

You wrote: Brachiopods, the phylum to which Lingula belongs, are one of those strange groups no one really knows where to place, although nowadays we are pretty sure they are somewhere in the general vicinity of molluscs, annelid worms and their ilk.

Does this imply that the completed genome sequence indicates that brachiopods don’t share a closer relation with bryozoa than molluscs?

This paper’s phylogenomic analyses put it as the sister group of molluscs, but molluscs and annelids are the only other lophotrochozoans in there. I’ve not heard of a sequenced bryozoan genome, and there doesn’t seem to be anything on the GOLD database.

Either way, “general vicinity of [stuff]” wasn’t really meant to imply anything more than that brachiopods are generally accepted as lophotrochozoans. There’s no way I’m taking sides re: their more precise whereabouts 😛

(BTW, supplementary figs 6-7 have summaries of which recent study put them where, which is really useful, since that’s something I can never remember off the top of my head 🙂 )

In response to the previous comment…I don’t think there is a bryozoan genome yet to compare it too…? CM will know better than I.

CM, to comment on your Lingula being really old… well, I know offhand that the extant Pterobranch genera (Cephalodiscus and Rhabdopleura) have nearly identical looking matches in the Cambrian fossil record (although I don’t know offhand if they are placed within those genera). I do think that morphological similarity/distinctiveness across time can be tested, and there has been some of that in the lingulids:

http://paleobiol.geoscienceworld.org/content/23/4/444.short

The first thing I noticed on Fig 2 was those incredible numbers. I’m really curious to see what happens whenever we get an articulate brachiopod genome or multiple articulate genomes (maybe a phoronid, if there is a god or gods). Linguilids/inarticulates are pretty weird brachiopods after all, so I’m curious to know if the long-branch-ness is them or its a brachiopod thing.If a pterobranch genome was ever done, it would be nice to know if it showed a lot of the excessive gain and loss that the linguilds showed.

There has apparently been a couple who’s mitochondrial genomes have been mapped.

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378111909001309

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1874778711000286

Ah, well, my point was that I didn’t think there was nuclear genome available for them to compare the brachiopod too.

Bryozoan nuclear genomes: AFAIK, you’re correct.

Morphology stuff: this is why I like having you around! 😀

Articulates and phoronids and pterobranchs? Hell yes, please, someone do all of that 😀 And make sure to look at articulate shell transcriptomes/proteomes while they’re at it 😛

There’s a cynical part of me that just shrugs and says all we’ll find in the shell transcriptome is more damned EGF and vWFA domains. (I might have developed a *slight* aversion to those two in the process of trying to identify interesting transcripts in my own data >_> Fucking BLAST fucking spitting out every fucking ECM protein ever when you’re just trying to find a Notch homologue. Grump.)